When Kika Ngakani fled the war-torn Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and came to Kakuma refugee camp in Kenya’s Turkana County in 2016, she was expecting a better life.

The frequent sound of gunshots, gory scenes of people maimed by the war, frightened women and children scampering to safety, and smoke billowing from burning houses were all behind her. However, shortly after settling in the Kalobeyei settlement in Kakuma, the harsh reality of life as a refugee in a foreign land struck the mother of six.

The Ksh1,600 monthly allowance called “Bamba Chakula,” typically used to cover the cost of basic food supplies, was not sufficient to cover all her needs, so Kika had to go on a job hunt, hoping to earn a wage to provide for her family.

However, her efforts to get employment were futile due to the language barrier. She could only speak French, which is the official language in her native country, while all potential employers wanted an individual who could communicate in English.

Without options, she decided to try her hand at farming despite having no prior experience. Luckily, the United Nations Food for Agriculture Organisation and the World Food Programme (WFP) were conducting a community training program on farming, which she enrolled in. Part of the training included a small parcel of farming land within the refugee settlement, and Kika set up a vegetable garden.

“I initially grew millet, but the crop did not do well, and we switched to vegetables after WFP constructed a water pan and provided us with greenhouses,” says Kika.

She saw a huge income-generating opportunity in vegetable farming, as vegetables were not readily available in the area. Local shops only stocked dry food items.

For Kika, vegetable farming paid off due to the readily available market. She saved some money to acquire additional parcels of land, but her plans to expand production were met by another hurdle—access to credit to prepare the land and buy farm inputs.

Like other refugees, she didn’t have an identification document to register with financial institutions. Additionally, getting a loan from such institutions required collateral, which she did not have. The informal lenders whom she occasionally engaged for short loans charged exorbitant interests.

Fortunately for Kika, a window of opportunity flung open after she learned about the Kenya Bankers Sacco (KBS) from a relative. “It was a surprise when I visited KBS offices in Kakuma town, and they enrolled me for the Jijenge Jiinua product with my manifest card. Since I was already earning regular income from the farm, I only saved for two months to qualify for a Ksh100,000 loan,” she explains with a broad smile. Through KBS, Kika has boosted her farming activities, earning enough to provide for her family and save for future projects.

She is all praise for KBS, saying: “Wanawake wengi hapa kambini wanategemea mabwana zao kushughulikia kila mahitaji ya familia lakini kwangu hakuna kitu kama hiyo. Niko na akaunti zangu binafsi na hizo mkopo zimenisaidia kuwekelea kwa mradi mbali mbali zinazonipatia faida (Many women within the camp are relying on their husbands to provide every family need, but that is not the case for me. I have my savings accounts, and the loans I access have helped me invest in the farm and other income-generation projects”.

KBS is a deposit-taking Sacco initially founded to cater to the needs of employees of small financial institutions but later opened to the public. It began its operations in Kakuma following a grant from the Kakuma Kalobeyei Challenge Fund (KKCF). In Kakuma, the institution focuses on the unbanked population, especially refugees, who have been excluded by mainstream financial institutions due to a lack of documentation and collateral.

According to a study by the International Finance Corporation (IFC) published in 2018, refugees own various shops, from open stalls to large wholesalers, but still face the challenge of limited access to credit, movement, and low financial literacy.

The refugees do not have the right to own property. This has practical implications, as a refugee business may not own the land it sits on or the fixed assets it has invested in. Additionally, banks are hesitant to provide credit to individuals or companies, as a lack of ownership means they lack collateral. Most refugees save at home or through a tontine, with the study findings suggesting that while those in the town save for positive outcomes, those in the camp do it as a coping strategy.

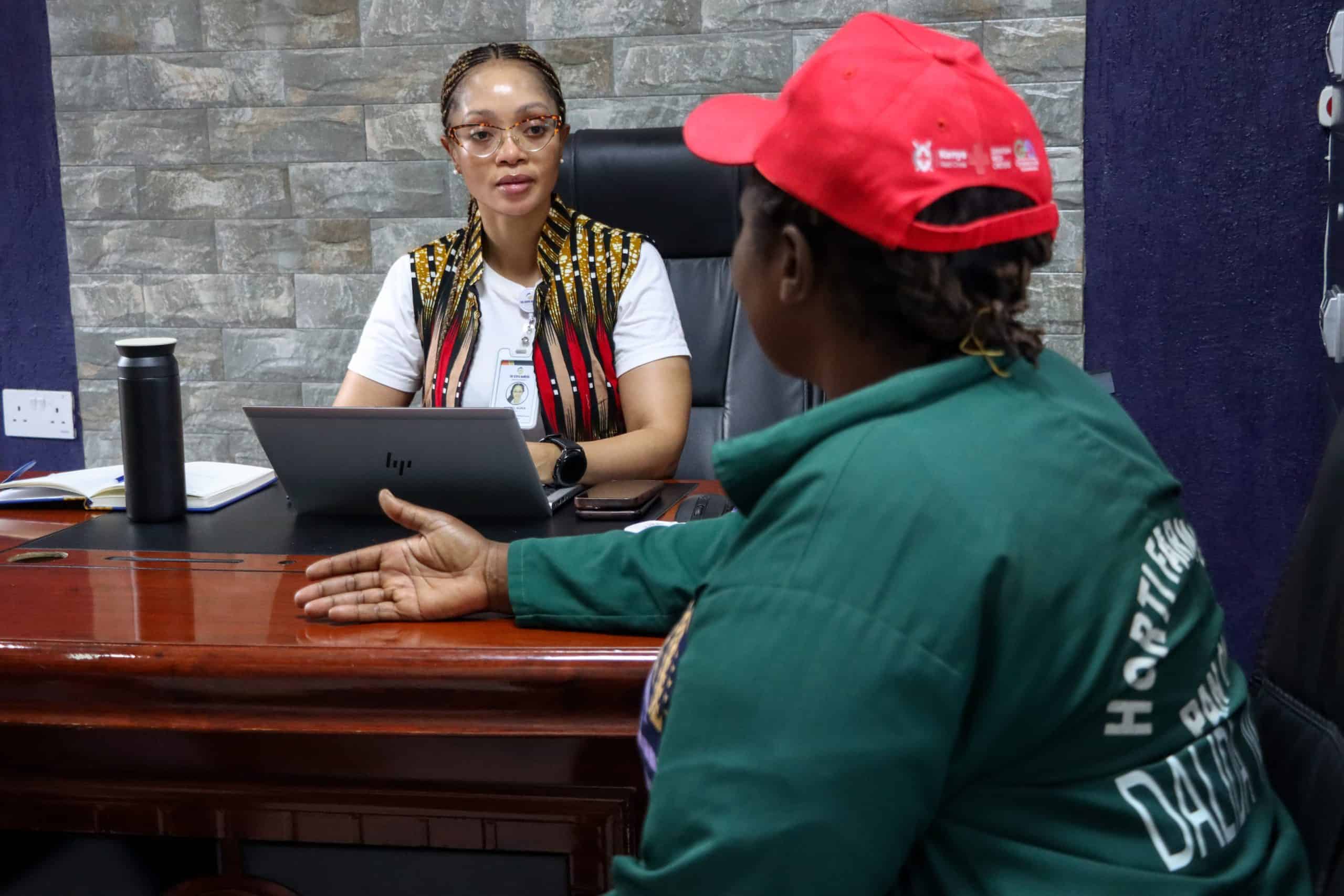

Mabel Auka, the Head of business development at KBS says the thriving economy in Kakuma and the high number of unbanked individuals offered a massive opportunity for financial services in the region. At the time, the Government had also rolled out a strategy dubbed the Shirika Plan to integrate refugees into society. Part of the plan entailed financial inclusion to empower them.

“When we did our research, we realized limited financial institutions or saccos were offering financial inclusion to the larger Turkana community, so we decided to bring our services closer to the people without discrimination,” says Auka.

KBS allows refugees to register for services with their manifest cards as a form of identification, enabling them to enjoy the benefits of a secure savings platform and access to loan facilities. Aside from funding, KKCF introduced KBS to the county government and the Department of Refugee Services, which allowed them access to the camp. KBS also received technical assistance in the form of training to help it better understand the market.

“While we had an idea of what we wanted to sell, it was difficult to sell a product that did not meet the market’s needs. KKFC helped to customize our products and services to the needs of our members,” explains Auka. The training also focused on compliance and reporting processes. Many youths have difficulty accessing employment opportunities and credit to engage in income-generating projects, yet they have great business ideas. KBS has been meeting them during our awareness and education sessions to understand and identify their unique needs. The institution has also launched specific products targeting women in small and medium-scale enterprises, chamas, and self-help groups. They have received training in financial literacy and business management, including bookkeeping and saving and investing wisely.

In Kakuma, cultural barriers discriminate against women’s economic empowerment. Culture dictates that while women bring resources, men determine how they are used.

“To avoid conflict between the two and concerning cultural norms, we train the women and encourage them to pass down the information to their spouses so that they both benefit from our services,” explains Auka.

Between January and October 2024, KBS lent over Ksh90m to about 3000 members, exceeding its target. Auka discloses that it plans to serve the larger Turkana and Northern Kenya communities that are underserved by formal banking institutions.

“We are adopting the agency banking model and will have agents in Kakuma town and Kalobeyei. We will recruit 17 agents to expand our services and net more people,” she says.