Manaliyo Deniza’s day starts early in the morning when she opens the heavy metal doors to her shop, located at Kalobeyei settlement in Kakuma refugee camp. After documenting the opening stock and placing new orders with the assistance of one of her employees, Deniza attends to customers and sorts out their purchases.

Deniza came from the Democratic Republic of Congo in 2011 and was processed and settled in Hong Kong, within Kakuma, before moving to the Kalobeyei settlement, where she set up the Maendeleo shop. She sells everyday essentials, including food, toiletries, and other household items. Before venturing into business, she worked as a casual laborer at several construction sites to support her family, but the daily wage was too little to meet her needs.

“Niliacha kufanya kazi ya mjengo na nikaingia kwa biashara ya kutembeza kitunguu na cabbages na nikafaulu kuweka pesa kidogo ya kukodisha duka ambapo nilianza kuuza bidhaa kadhaa (I quit my job at construction sites to hawk onions and cabbages from door to door. This enabled me to save enough money to rent a small shop where I started selling assorted products),” she says.

Deniza desired to establish herself as a leading entrepreneur in the community, offering a variety of goods to locals, refugees, and the host community. However, realizing this dream was not possible as she lacked capital and business management skills.

Her breakthrough, however, came four years ago when she was introduced to the Kakuma Kalobeyei Challenge Fund (KKCF). Although Deniza was among the first refugee traders to seek a grant from the fund, her hopes were dashed after her application was set aside because it failed to meet the requirements. However, she succeeded on the second trial after undergoing a seven-week accelerator program that equipped her with, among other skills, the knowledge and skills to draw a business plan and a concept note for the grant.

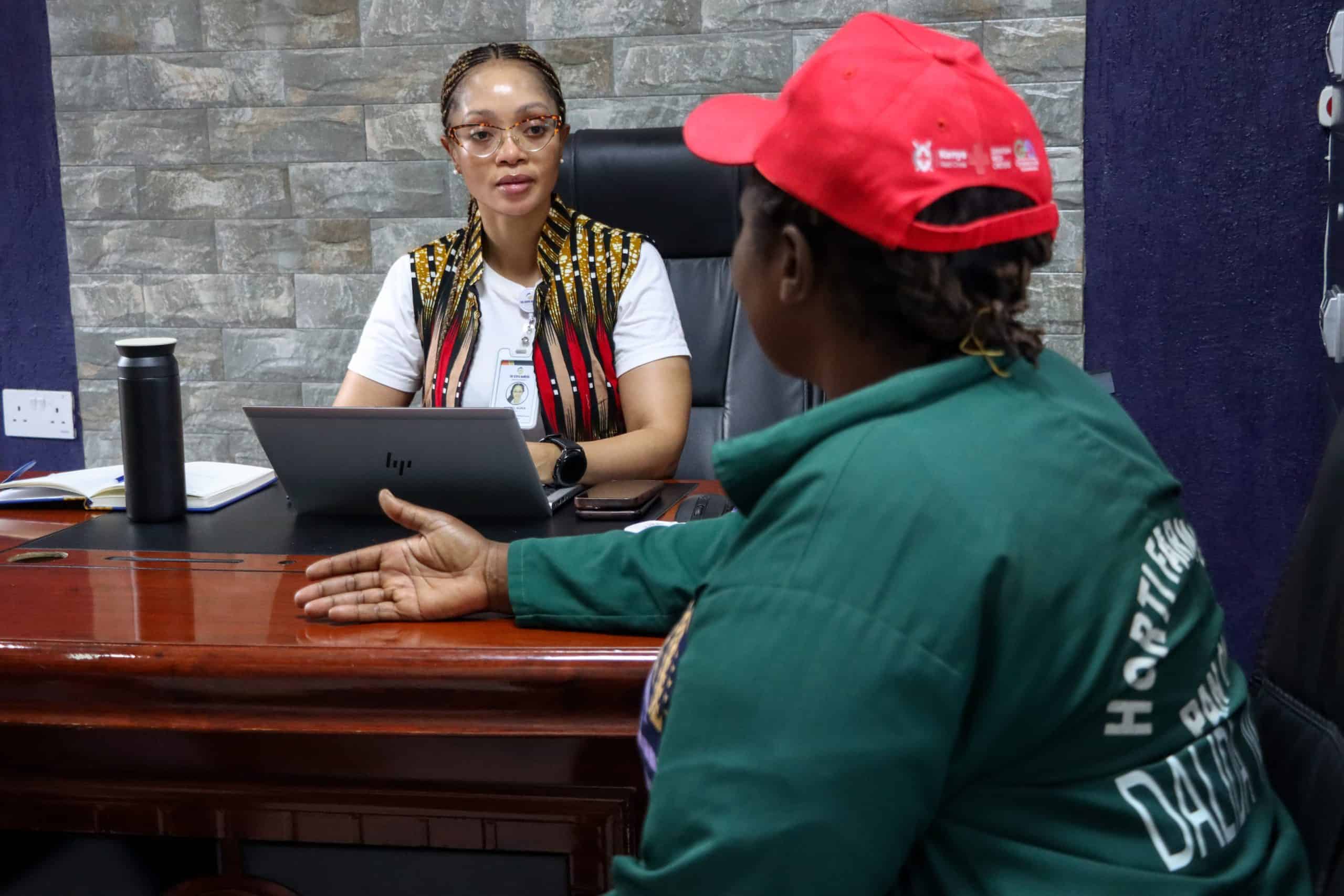

“Nilipigiwa simu niende kwa ofisi na nikaambiwa nimechaguliwa miongoni wa wafanyibiashara wenye watapewa mafunzo jinsi ya kufanya business plans, kuweka records za biashara na vile tunavyo fanya marketing na kufanya hesabu ya bei ya vitu na expenses ndio tueze kupata faida kwa kuuza (I received a phone call asking me to go for a meeting at the office where they informed me that I was among the applicants who will attend a seven-week training on business management, marketing, and branding and how to cost our products after calculating cost of the goods and expenses so that we get profits),” she says.

Through the grant, Deniza rented a more spacious shop and introduced a variety of goods, which she also sold to other traders at wholesale prices. The training has helped Deniza run a successful business, making enough money to save for future expansion and meet family needs. She currently employs six people – five refugees and one from the host community. “Wakimbizi wako na changamoto mengi na wale wenye hawana kazi unapata wanaingia kwa mienendo mabaya kwa uwizi na ndio maana najitahidi kuwapatia ndio wawena nguvu ya nkusaidia familia zao kazi (Refugees face many challenges, and some with no jobs end up engaging in wrong vices, including crime. I always work hard to create jobs to empower them so that they can provide for their families,” she narrates.

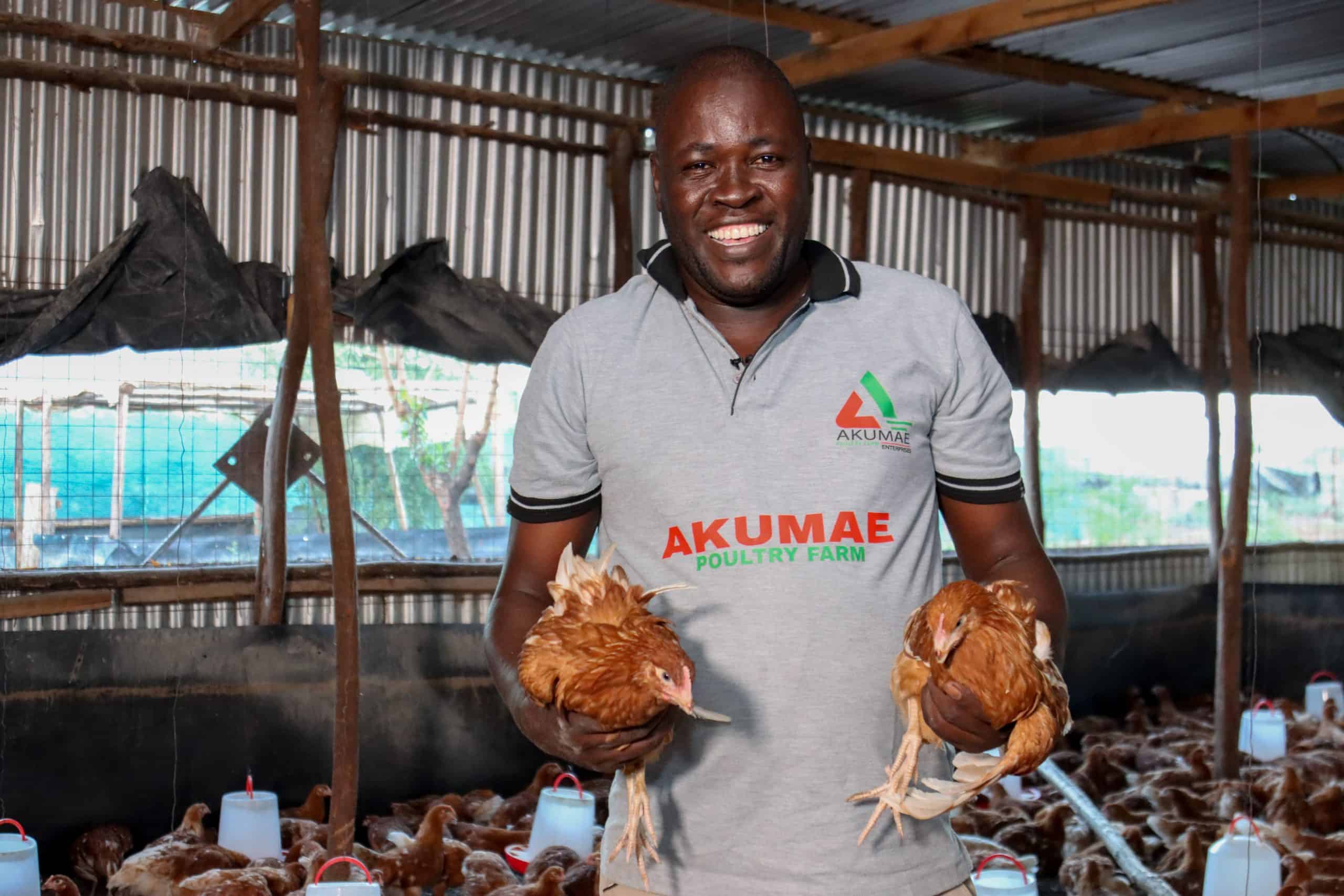

Deniza’s story is a testament to the resilience and entrepreneurial spirit of the refugee population. Many of them have defied the odds by starting thriving small-scale businesses to tap the US$56 million economy at the Kakuma camp to generate income and meet their needs.

Under KKCF’s Local Enterprise Development (LED) window, the program focuses on local businesses that have the potential to create employment within the refugee and host communities and impact the economy.

“When you look at the refugees and the host community, you find that most of the businesses they operate are micro and small-scale, and the owners have very little or no business management skills to succeed. What this meant is that we needed to support them to acquire the necessary skills and provide them with a grant to boost their businesses,” says Brian Murithi, KKCF Program Manager, adding that this approach has created much impact and led to the economic integration of the refugees and host community.

Because of Deniza’s business success and contribution to the local economy, she has earned a special place among her peers within the refugee and host community. She sits on several development committees and is always invited to meetings where the community welfare is discussed.

She wants to upgrade into a self-service store to serve the community better by offering products at low costs and employing more people, especially women. “When you give a woman a job, you empower the whole community, as they are the ones who have huge responsibilities within the families,” she says.